sovote.ca

This website is under development

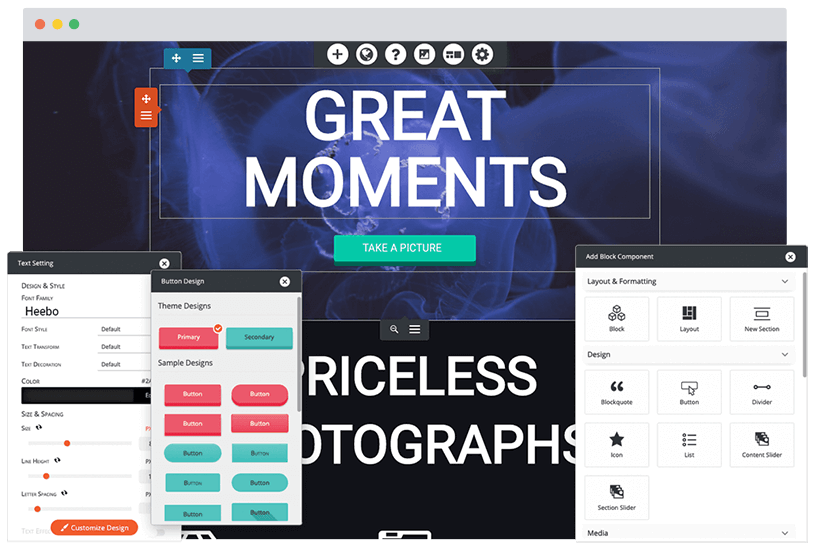

Build a better website

Managed WordPress Hosting

Get fast, secure, managed hosting, including an easy-to-use WordPress Website Builder to design like a professional.

Plans from CAD $6.99/mo

Choose a Plan